Nomination for a Best of the Net Award.

Formless text for the poem/s:

Poem 1 = entire grid

Poem 2 = inner circle, central vision that’s left

Poem 3 = Blind Ring

Poem 1

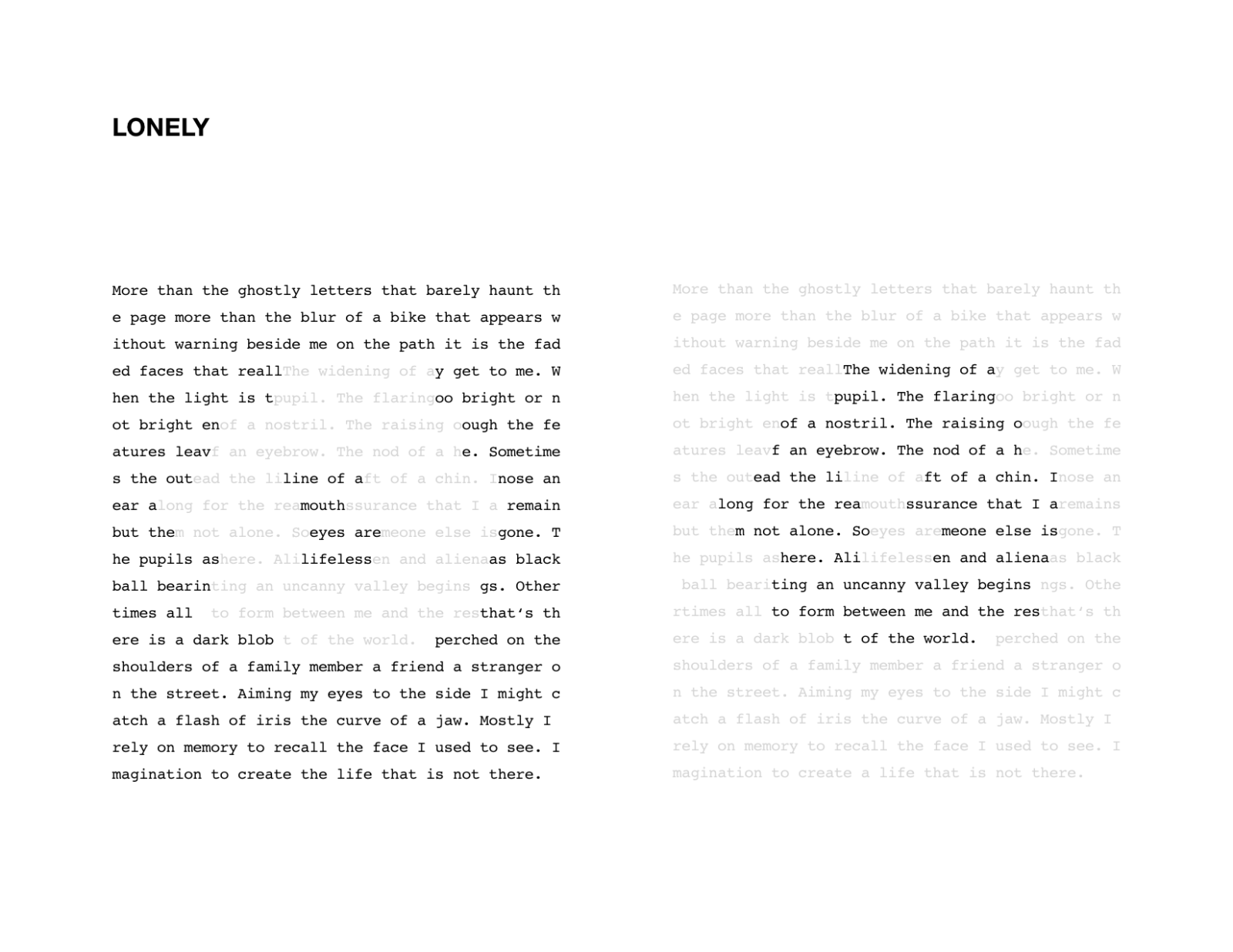

More than the ghostly letters that barely haunt the page more than the blur of a bike that appears without warning beside me on the path it is the faded faces that really get to me. When the light is too bright or not bright enough the features leave. Sometimes the outline of nose an ear a mouth remain but the eyes are gone. The pupils as lifeless as black ball bearings. Other times all that’s there is a dark blob perched on the shoulders of a family member a friend a stranger on the street. Aiming my eyes to the side I might catch a flash of iris the curve of a jaw. Mostly I rely on memory to recall the face I used to see. Imagination to create the life that is not there.

Poem 2

line of a

mouth

eyes are

lifeless

Poem 3

The widening of a pupil. The flaring of a nostril. The raising of an eyebrow. The nod of a head the lift of a chin. I long for the reassurance that I am not alone. Someone else is there. Alien and alienating an uncanny valley begins to form between me and the rest of the world.

Resources and Additional Thoughts

The first sentence of my mood poem echoes this sentence:

More than the fuchsia funnels breaking out

Instructions on Not Giving Up/ Ada Limón

of the crabapple tree, more than the neighbor’s

almost obscene display of cherry limbs shoving

their cotton candy-colored blossoms to the slate

sky of Spring rains, it’s the greening of the trees

that really gets to me.

Face Blindness: prosopagnosia, a brain disorder characterized by the inability to recognize faces. I do not have prosopagnosia, but with my deteriorating central vision, I frequently cannot recognize people. I wrote the following in a log entry, as I worked on this mood poem:

One of the biggest struggles I’m having with my vision loss is how to interact with others. I can’t see faces clearly. Often I can see some features but I can’t see when someone is looking at me or talking to me and even if I can tell they’re talking to me, there’s a good chance I won’t recognize them. I haven’t figured out how to deal with how unsettling and upsetting this is yet, so I try to avoid it. It’s much easier during this pandemic. What a relief to not have to try and interact with others! How much easier it is to not have to wonder if someone was talking to me or what they said or who they are! I like talking with people and I sometimes miss interesting conversations with new people, but mostly I’m content not talking with others, being left alone.

This morning, I read someone’s account of their face blindness and I could really relate. Face blindness is not my primary diagnosis; it’s just a byproduct of my vision loss and the big blind spot (or, what I’m calling, blind ring) in the center of my vision. There’s a lot I could highlight from this article–dreading encountering other moms that I can’t recognize, not being able to identify my kids, not seeing my husband walk past me in a store, only being able to recognize people by their distinctive quirks.

It is with our faces that we face the world, from the moment of birth to the moment of death. Our age and our gender are printed on our faces. Our emotions, the open and instinctive emotions that Darwin wrote about, as well as the hidden or repressed ones that Freud wrote about, are displayed on our faces, along with our thoughts and intentions. Though we may admire arms and legs, breasts and buttocks, it is the face, first and last, that is judged “beautiful” in an aesthetic sense, “fine” or “distinguished” in a moral or intellectual sense. And, crucially, it is by our faces that we can be recognized as individuals.

Oliver Sacks/ Face-Blind

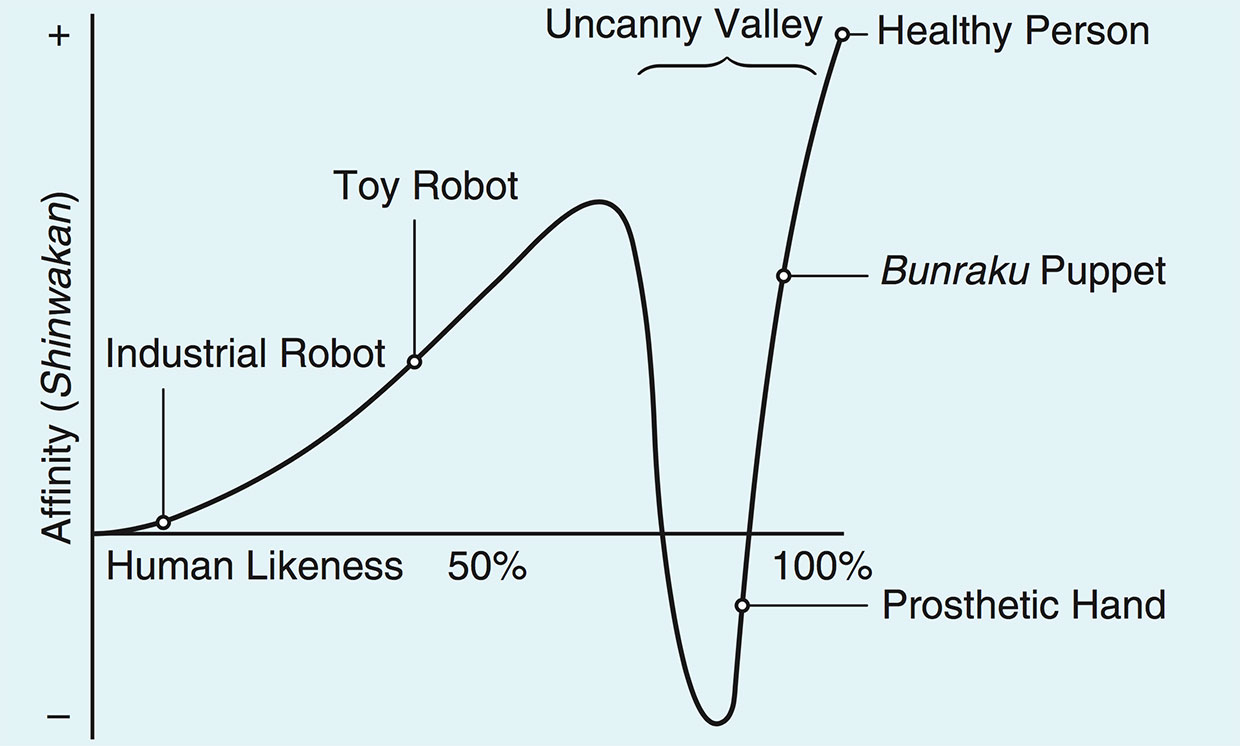

The uncanny valley graph created by Masahiro Mori: As a robot’s human likeness [horizontal axis] increases, our affinity towards the robot [vertical axis] increases too, but only up to a certain point. For some lifelike robots, our response to them plunges, and they appear repulsive or creepy. That’s the uncanny valley.

Rina Diane Caballar discussing Masahiro Mori’s uncanny valley

For several years, I’ve wanted to write about the uncanny valley and my feelings of alienation–partly because I can’t see others seeing me which makes me feel not quite human, and partly because I can’t see others’ pupils which makes me feel like no one else is human/”real”; I’m the only one. In the fall of 2019, I started writing about some awesome images of Minnesota State Fair mannequins that my husband Scott took, exploring why and how they’re not quite human, yet delightful to me:

(from log entry on sept 5, 2019 ): Looked up uncanny valley and found this definition: “a distinctive dip in the relationship between human-likeness and emotional response.” What makes us human? Or, what makes us see each other as human, makes us feel empathy for each other? Is it the eyes? The pupils? The spark within that black ball?

I have trouble seeing people’s pupils. Can I ever see that spark? Do I imagine one? Sometimes everyone feels like a mannequin to me. Not quite human. Not alive or there. And sometimes mannequins feel human, like this girl.

Link: The Uncanny Valley: The Original Essay by Masahiro Mori

(from my notes in 2019): One of the first things the ophthalmologist told me when I was diagnosed with cone dystrophy was that I’d need to learn to look just past people’s shoulders if I wanted to see their faces. Once my central vision was gone, I would only be able to see them through my peripheral. How unsettling is it to others to look at them this way? I do not look at people’s shoulders…yet. For now, I either avoid looking or I just stare into their dim, fading, dead-pupil faces and pretend that they don’t look like a lifeless mannequin.