An Introduction

In August of 2016, at the age of 42, I was diagnosed with macular dystrophy. Two years later, the diagnosis was narrowed to cone dystrophy and I was told that I would lose all of my central vision within the next five years. Since then, I’ve been researching and writing about my vision loss. In the fall of 2018, I completed a series of poems about my experiences trying to keep swimming across my neighborhood lake as I struggled to see: How to Be When You Cannot See. In the spring of 2019, I did another series of poems that I fit into the form of Snellen Charts about my diagnosis and how I experience cone dystrophy: when i cannot see straight i will see sideways. My current project, Mood Rings, written this fall (2020), is a series of poems using the form of the blind spot in my central vision and the Amsler grid to express how it feels to be in-between seeing and being (legally) blind.

Finding My Blind Spot

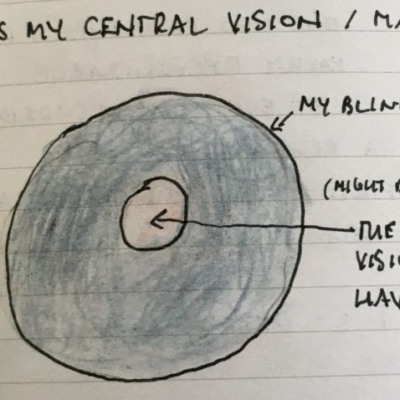

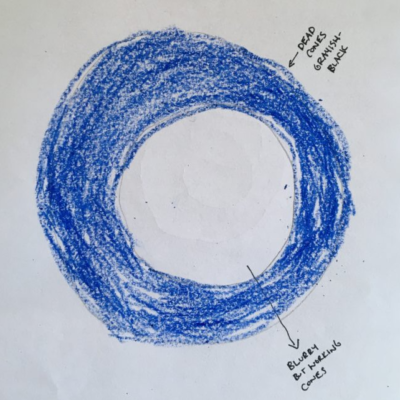

(which isn’t a spot but a ring)

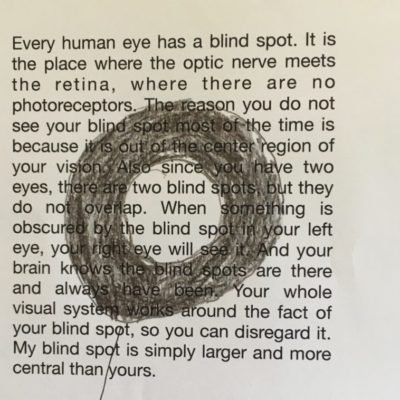

Just before the pandemic hit, I started reading Georgina Kleege’s Sight Unseen. In the chapter, “The Mind’s Eye,” she describes how she finds the blind spot in her central vision by staring at a blank wall.

With effort, I can force myself to see my blind spot. When I stare directly at a blank wall, this flaw in my retina does not appear as a black hole or splotch of darkness. When I am very tired I see an irregularly shaped blotch, which throbs slightly and is either an intense blue-violet, or a deep teal green. More often, I see a blur slightly darker in color than the wall overlay with a pattern of tiny flecks. Depending on lighting conditions these flecks are bright white, sometimes edged in violet or a golden yellow.

This description inspired me to try and find my blind spot. I went to a blank wall in my living room, stood still, and stared at it. Eventually I saw something strange. It wasn’t a full spot but a dark ring with a light center. I tried drawing it from memory in my notebook. In August, I returned to the ring. I taped a piece of paper to the wall at eye level, closed one eye, and then traced the blind ring that appeared, first with a pencil, later with blue crayon.

I was amazed and delighted to see this ring. Finally evidence of declining vision that I could observe! I knew I was losing central vision by how much harder it was to read, how people’s faces were fuzzy blurs, how I never noticed mold, but my brain was compensating remarkably well and I often wondered if I was just making it up.

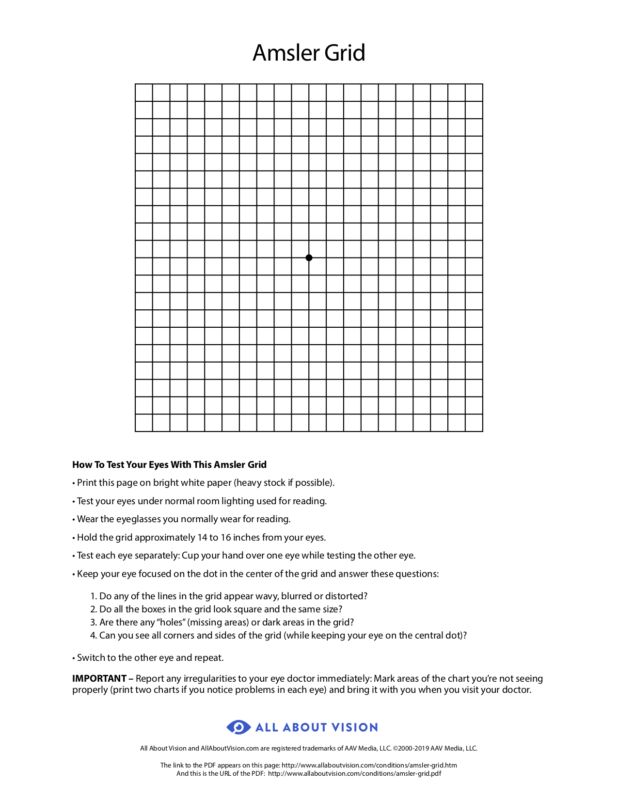

Before seeing my blind ring on the wall, the main method I used for checking up on my sight was to stare into the Amsler grid, which doctors use to detect damage to the macula. I would notice how the lines were wavy instead of straight, faded a few blocks from the center, not sharp, and I could reassure myself that I wasn’t making up my failing vision. But, seeing the ring on the wall, made the vision loss more dramatic and real.

Experimenting with Form

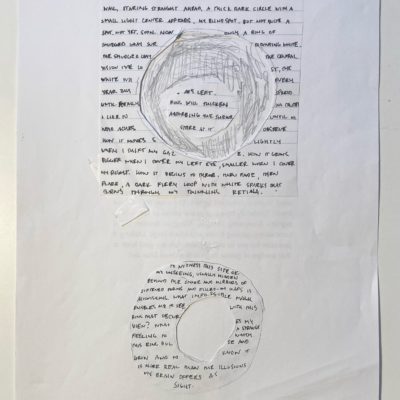

I decided to use these forms–my blind ring and the Amsler grid–for some poems about living in the in-between state of not quite seeing, not yet (legally) blind. And I decided to focus on how I felt and the moods I experienced in this state. It seemed urgent and important to try and identify and carefully study these moods and then find ways to express them, partly because I needed to work through my feelings, and partly because I wanted to give attention to something that wasn’t discussed enough: what it feels like to be in the process of losing sight/central vision. Not after it is lost or before, but during.

I had been thinking about what these poems might become for a while, but during a run on August 28th, it finally came to me: moods and mood rings! Here are some notes I recorded at the end of that run:

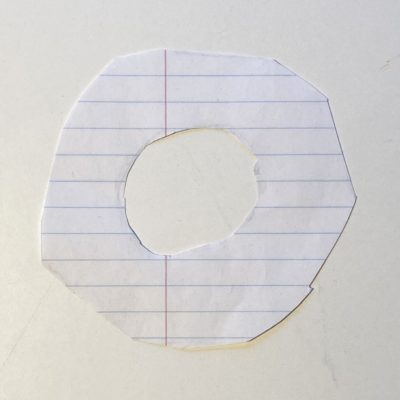

I experimented with different ways to use the ring on a block of justified text that was roughly the size of the Amsler grid. I drew it directly on the text, almost like an erasure poem in which you black out text to create a new poem. Next I tried making the letters that fell into the blind spot much lighter in font color so they almost disappeared. Then I traced the ring on a piece of paper, cut it out, and placed it over text, both on paper and on my computer screen. And I cut out another ring and the small circle of central vision I have left, taped them on to a sheet of paper, and then wrote the text of a poem on the ring and in the circle. I also tried turning the boxes of the Amsler grid into letters from the repeating phrases, “the site of my unseeing” and “uncanny valley.”

3 Poems in One Grid

Finally, when none of these methods quite worked, I decided to create a grid, 50 columns by 18 rows, and fit 3 poems describing a mood into it: a main poem that was in the form of my overall working vision, a smaller poem that was in the form of the central vision within the blind ring that I still have left, and a hidden poem with words filling in the boxes in the space of my blind ring.

Each box contains one character (a letter or space or punctuation) and I use a monotype font to keep it evenly spaced. The tedious process of trying to fit the poem in the boxes and to create a second inner poem with words that were also part of the first poem has been a helpful challenge that is enabling me to make my ideas and words for expressing them more precise and compelling and exciting (at least to me).

Check out my resources page for more information about my research, sources of information, etc. Also, check out my discussion of thinking through the project on my running log.